1. Overview

PostgreSQL is a great open source database, and many users chose it because of the efficiency of its central algorithms and data structures. As a software developer, I was always curious about how each part was done, such as the physical files storage. The reason is that I always see a lot of files and folders were created after a simple initdb command. For example,

1 | $ ls -ltr /home/user/pgdata |

I can do a simple command like below to check the file PG_VERSION, but what about the rest of the files and folders?

1 | $ cat /home/user/pgdata/PG_VERSION |

In this blog, I am going to share what I learned about the heap files under base folder.

1. How the Heap files are created?

To explain this, let’s take a look at two key data structures.

RelFileNodedefined insrc/include/storage/felfilenode.h.Where,1

2

3

4

5

6typedef struct RelFileNode

{

Oid spcNode; /* tablespace */

Oid dbNode; /* database */

Oid relNode; /* relation */

} RelFileNode;spcNodeis the tablespace oid,dbNodeis the database oid, andrelNodeis table oid. The table oid will be used as the file name to create the corresponding heap file. However, the Heap files will not be created unless you insert the first record to the table. For example,You will see the heap files under the database folder like below,1

2postgres=# create table orders1 (id int4, test text) using heap;

postgres=# insert into orders1 values(1, 'hello world!');Where 16384 is the table orders1’s oid. To verify it, there is a built-in function1

2

3

4$ ls -ltrh /home/user/pgdata/base/12705/16384*

-rw------- 1 user user 24K Oct 8 14:33 /home/user/pgdata/base/12705/16384_fsm

-rw------- 1 user user 8.0K Oct 8 14:34 /home/user/pgdata/base/12705/16384_vm

-rw------- 1 user user 512K Oct 8 14:34 /home/user/pgdata/base/12705/16384pg_relation_filepathwhich returns the first heap file segment with a relative path to the environment variable PGDATA. For example,1

2

3

4

5postgres=# SELECT pg_relation_filepath('orders1');

pg_relation_filepath

----------------------

base/12705/16384

(1 row)ForkNumberdefined in src/include/common/relpath.h.Where,1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8typedef enum ForkNumber

{

InvalidForkNumber = -1,

MAIN_FORKNUM = 0,

FSM_FORKNUM,

VISIBILITYMAP_FORKNUM,

INIT_FORKNUM

} ForkNumber;MAIN_FORKNUMrepresents heap files,FSM_FORKNUMrepresents free space mapping files, andVISIBILITYMAP_FORKNUMrepresents visibility mapping files. In above example, the physical files map to the enum valuesMAIN_FORKNUM,FSM_FORKNUMandVISIBILITYMAP_FORKNUMare 16384, 16384_fsm and 16384_vm correspondingly. The rest of this blog will focus onheap file.

2. How the Heap files are managed?

Heap file, as the fork name MAIN_FORKNUM indicated, is the main file used to store all the data records. The heap file will be divided into different segments when it exceeds 1GB that is the default settings. The first file is always named using the filenode (table oid), and subsequent segments will be named as filenode.1, filenode.2 etc. In theory, the segmentation rule also applies to free space mapping and visibility mapping files, but it seldom happens since free space mapping file and visibility mapping file are not increasing as fast as heap files.

3. How does a Page look like?

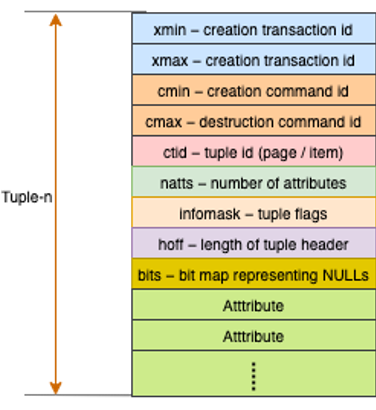

To make the data management easier, each heap file is splitted into different pages with a default size 8KB. The data structure for each page is defined by below data structures:

ItemIdData

1

2

3

4

5

6typedef struct ItemIdData

{

unsigned lp_off:15, /* offset to tuple (from start of page) */

lp_flags:2, /* state of line pointer, see below */

lp_len:15; /* byte length of tuple */

} ItemIdData;ItemIdData is the line pointer in a page, which is defined in

src/include/storage/itemid.h.HeapTupleFields

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11typedef struct HeapTupleFields

{

TransactionId t_xmin; /* inserting xact ID */

TransactionId t_xmax; /* deleting or locking xact ID */

union

{

CommandId t_cid; /* inserting or deleting command ID, or both */

TransactionId t_xvac; /* old-style VACUUM FULL xact ID */

} t_field3;

} HeapTupleFields;HeapTupleFields is part of the header for each tuple, defined in

src/include/access/htup_details.h.HeapTupleHeaderData

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29struct HeapTupleHeaderData

{

union

{

HeapTupleFields t_heap;

DatumTupleFields t_datum;

} t_choice;

ItemPointerData t_ctid; /* current TID of this or newer tuple (or a

* speculative insertion token) */

/* Fields below here must match MinimalTupleData! */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_INFOMASK2 2

uint16 t_infomask2; /* number of attributes + various flags */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_INFOMASK 3

uint16 t_infomask; /* various flag bits, see below */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_HOFF 4

uint8 t_hoff; /* sizeof header incl. bitmap, padding */

/* ^ - 23 bytes - ^ */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_BITS 5

bits8 t_bits[FLEXIBLE_ARRAY_MEMBER]; /* bitmap of NULLs */

/* MORE DATA FOLLOWS AT END OF STRUCT */

};HeapTupleHeaderData is the tuple data structure, defined in defined in

src/include/access/htup_details.h.

A high level picture for a tuple looks like the picture below.

But, this may be still hard to understand for an end user. Don’t worry, PG provides an extension pageinspect.

4. The extension for Page

The pageinspect extension provides the functions that allow you to inspect the contents of database pages at a low level, which is very useful for debugging purposes. Here are the main functions provided by pageinspect. To use this extension, you have to install it first, and then add it to your PG server. For example,

1 | postgres=# create extension pageinspect; |

Here are the functions for heap page:

- heap_page_items

heap_page_itemsreturns all the records within given page. It includes line pointers, tuple headers as well as tuple raw data, i.e.lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_data.

All the tuples will be displayed at the moment when the page is loaded from heap file into buffer manager, no matter whether the tuple is visible or not. For example,1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11postgres=# insert into orders1 values(generate_series(1, 200), 'hello world!');

INSERT 0 200

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('orders1', 0));

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_data

-----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+---------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+--------------------------------------

1 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,1) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x010000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

2 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x020000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

3 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,3) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x030000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

4 | 8000 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x040000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

5 | 7952 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,5) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x050000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

6 | 7904 | 1 | 41 | 691 | 0 | 0 | (0,6) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | \x060000001b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421

- tuple_data_split

tuple_data_splitsplits tuple data into attributes and returns bytea array. For example,1

2

3

4

5

6postgres=# SELECT tuple_data_split('orders1'::regclass, t_data, t_infomask, t_infomask2, t_bits) FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('orders1', 0));

tuple_data_split

-------------------------------------------------

{"\\x01000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

{"\\x02000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

{"\\x03000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

- heap_page_item_attrs

heap_page_item_attrs is equivalent to heap_page_items except that it returns tuple raw data as an array of attributes. For example,

1 |

|

- heap_tuple_infomask_flags

heap_tuple_infomask_flagswill help decode the tuple header attributes, i.e.t_infomaskandt_infomask2into a human-readable set of arrays made of flag names, with one column for all the flags and one column for combined flags. For example,1

2

3

4

5

6postgres=# SELECT t_ctid, raw_flags, combined_flags FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('orders1', 0)), LATERAL heap_tuple_infomask_flags(t_infomask, t_infomask2) WHERE t_infomask IS NOT NULL OR t_infomask2 IS NOT NULL;

t_ctid | raw_flags | combined_flags

---------+----------------------------------------------------------+----------------

(0,1) | {HEAP_HASVARWIDTH,HEAP_XMIN_COMMITTED,HEAP_XMAX_INVALID} | {}

(0,2) | {HEAP_HASVARWIDTH,HEAP_XMIN_COMMITTED,HEAP_XMAX_INVALID} | {}

(0,3) | {HEAP_HASVARWIDTH,HEAP_XMIN_COMMITTED,HEAP_XMAX_INVALID} | {}

5. What happens on heap page when performing insert, delete and vacuum

Now, we have learned something about heap file and the page inspect extension. Let’s see how the tuples are managed when user performs some insert, delete and vacuum on a table.

Insert

First, let insert 200 records to a brand new table orders1,1

2postgres=# insert into orders1 values(generate_series(1, 200), 'hello world!');

INSERT 0 200then use the function

heap_page_item_attrsto see how the page looks like,1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 0), 'orders1'::regclass);

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_attrs

-----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+---------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+-------------------------------------------------

1 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,1) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x01000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

2 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x02000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

3 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,3) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x03000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

... ...

155 | 752 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,155) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x9b000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

156 | 704 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,156) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x9c000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

157 | 656 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (0,157) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x9d000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

(157 rows)

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 1), 'orders1'::regclass);

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_attrs

----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+--------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+-------------------------------------------------

1 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,1) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x9e000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

2 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,2) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x9f000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

3 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,3) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\xa0000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

... ...

41 | 6224 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,41) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\xc6000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

42 | 6176 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,42) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\xc7000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

43 | 6128 | 1 | 41 | 591 | 0 | 0 | (1,43) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\xc8000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

(43 rows)As you can see, after 200 records were inserted, PG created two pages: the 1st page has 157 tuples, and the 2nd page has 43 tuples. If you try to access the 3rd page, then you will some errors like below,

1

2postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 2), 'orders1'::regclass);

ERROR: block number 2 is out of range for relation "orders1"Delete

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11postgres=# delete from orders1 where id%2=1;

DELETE 100

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 0), 'orders1'::regclass);

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_attrs

-----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+---------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+-------------------------------------------------

1 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 599 | 0 | (0,1) | 8194 | 258 | 24 | | | {"\\x01000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

2 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x02000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

3 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 599 | 0 | (0,3) | 8194 | 258 | 24 | | | {"\\x03000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

4 | 8000 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x04000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

5 | 7952 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 599 | 0 | (0,5) | 8194 | 258 | 24 | | | {"\\x05000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

6 | 7904 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,6) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x06000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}Now, for all the odd records, the

t_maxpoints to a different transaction (delete) id, andt_infomask2indicates the tuple has been deleted. For more detailed information, please checkt_infomask2definition.Insert a new record

If you insert a record now, you will find the new record is inserted into the first empty slot. In this example, the first line\\xe8030000is the new record withid=1000.1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11postgres=# insert into orders1 values(1000, 'hello world!');

INSERT 0 1

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 0), 'orders1'::regclass);

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_attrs

-----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+---------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+-------------------------------------------------

1 | 4400 | 1 | 41 | 601 | 0 | 0 | (0,1) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | {"\\xe8030000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

2 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x02000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | | | | | | | | |

4 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x04000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | | | | | | | | |

6 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,6) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | {"\\x06000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

The t_min points to the new transaction (insert) id, and t_max is cleared to indicate this is a valid record.

- Vacuum

Let’s perform a vacuum on this table only, and then insert another new record,id=1001.

1 | postgres=# vacuum orders1; |

The result shows the 2nd new record id=1001 is inserted to the 3rd place, and we don’t see any different after vacuum orders1 was executed.

- Vacuum full

Now, let’s run a vacuum full, and insert the 3rd new record,After the1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23postgres=# vacuum full;

VACUUM

postgres=# insert into orders1 values(1002, 'hello world!');

INSERT 0 1

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 0), 'orders1'::regclass);

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_attrs

-----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+---------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+-------------------------------------------------

1 | 8144 | 1 | 41 | 601 | 0 | 0 | (0,1) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\xe8030000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

2 | 8096 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\x02000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

3 | 8048 | 1 | 41 | 602 | 0 | 0 | (0,3) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\xe9030000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

4 | 8000 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\x04000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

5 | 7952 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,5) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\x06000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

6 | 7904 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,6) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\x08000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

... ...

100 | 3392 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,100) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\xc4000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

101 | 3344 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,101) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\xc6000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

102 | 3296 | 1 | 41 | 598 | 0 | 0 | (0,102) | 2 | 2818 | 24 | | | {"\\xc8000000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

103 | 3248 | 1 | 41 | 676 | 0 | 0 | (0,103) | 2 | 2050 | 24 | | | {"\\xea030000","\\x1b68656c6c6f20776f726c6421"}

(103 rows)

postgres=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_item_attrs(get_raw_page('orders1', 2), 'orders1'::regclass);

ERROR: block number 2 is out of range for relation "orders1"vacuum full, there are some changes,

1) all dead tuples were removed, the rest tuples were shuffled and merged into the 1st page, and the 2nd page was deleted.

2) the new record 1id=10021 was inserted to the very end.

3) No access to the 2nd page, since it has been deleted.

This extension provides an easy way to observe how a heap page is changed when performing insert, delete and vacuum. The same behaviour can be observed on the heap file when using hexdump command (checkpoint may require to force the memory page to be flushed to heap file after each operation).

6. Summary

We explained how the heap files are created, the internal data structure of heap file and page (a segment of a heap file), and demonstrated how to use the extension pageinspect to check what happens when user performed some insert, delete and vacuum. In the coming blogs, I will explain the free space mapping file and the visibility mapping file in the same way.